Chasing Shadows

In the realm of pop culture, the stories of celebrities tend to develop a life of their own. Rock stars, famous rappers and activists are all shrouded in a mystical halo, making everything they ever did either point to their inevitable success or failure. The same applies to famous criminals. It would be naïve to assume that our perception of convicted murderers and rapists remains unchanged as soon as they are dipped into Hollywood limelight, wrapped into layers of representation, the faces of actors superimposed upon their own. One interesting question to ask is why people who commit such atrocities even spark fascination in the first place. Why even dive into that rabbit hole of human abyss?

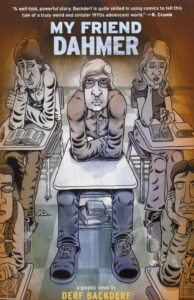

The answer of Derf Backderf, the U.S. cartoonist behind the 2012 graphic memoir My Friend Dahmer would probably be relatively simple: He knew the guy. Backderf went to the same high school as Jeffrey Dahmer, the teenager who would later in his life murder, rape and mutilate 17 males before being killed by a fellow inmate in prison in 1994. Backderf’s comic looks back to a time before these horrible crimes were committed, to his own high school days in 1970’s Ohio in order to get closer to Dahmer as a person. As stated in the comic’s foreword, the intent of the work is not to excuse the actions of his school friend but to contextualize them, to show that the transformation of the shy and severely troubled teenager into a mass murderer was not set in stone and could perhaps have been avoided.

This attempt to humanize a person whose later actions were unspeakably violent and deranged, to add a perspective to the story that suspends judgement and strives for understanding, is constantly under threat within the comic. This is a memoir, not a psychological report, and despite a visible aim for clarity, Backderf’s graphic memories of Dahmer and his high school days are always steeped in emotion and presented by a very prominent narrator. One might even say that there are two conflicting perspectives within the comic: there is one in which Backderf recounts his own personal memories of Dahmer as a teenager, who traces their parallel trajectories from adolescence to adult life, recounts their shared time in hallways, during lunch breaks and car rides. And then there is another in which the narrator attempts to ‘fill in the blanks’ with the help of criminal records and interviews to understand the struggles of Dahmer and the events to which Backderf was oblivious at the time.

The way that these levels blend into each other may be one of the comic’s greatest strengths. Backderf draws parallels between his life and Dahmer’s and thereby asks meaningful questions concerning the forces that shape us in our upbringing and the extent of our own personal freedom. By describing to the peculiarities of 1970’s rural Ohio he points to the paradox of a tight-knit neighborhood that is simultaneously inert when it comes to helping people who are obviously in desperate need, whether this be Dahmer himself or his severely ill mother. In the comic, Dahmer is presented as a vulnerable and isolated figure, neglected by his self-absorbed parents, and isolated from his peers first by his growing mental instability. However, he is also an enigma, a person retreated to far into himself that his personality is hardly more than a small shadow in the corner of a room. The only time Dahmer drew any attention in school was in his role as ‘class clown’ who briefly amused high fellow students (including Backderf) with his antics.

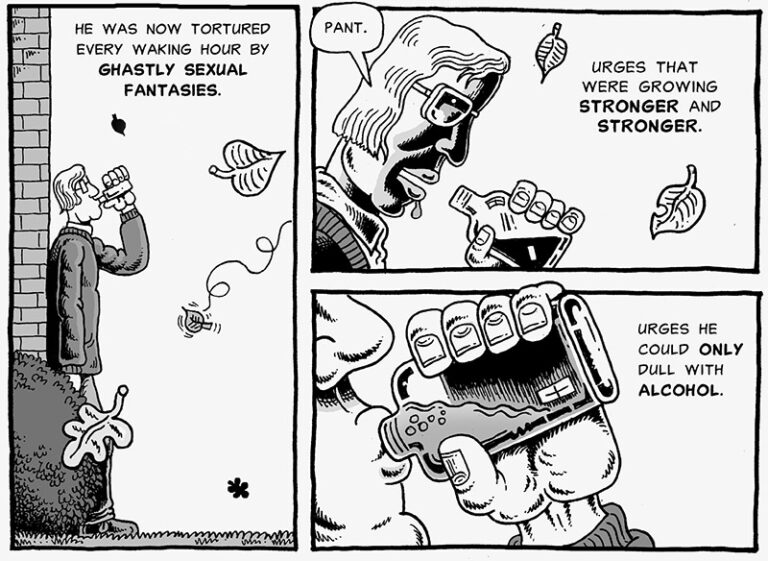

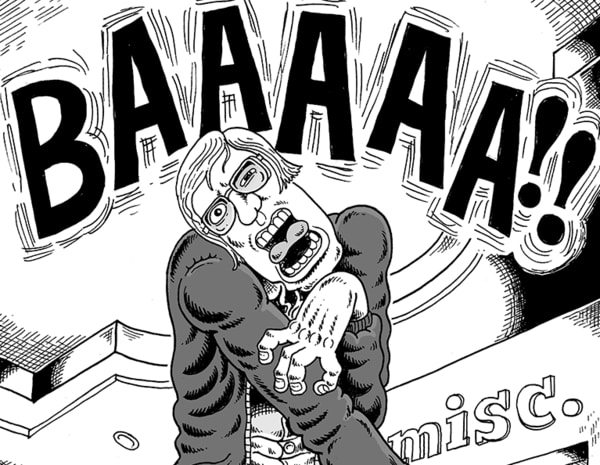

The inscrutability of Dahmer is mostly conveyed by the drawings which present the face of the troubled teenager as a cold mask, almost devoid of any emotion except for the grotesque grimaces during his pranks. In general, Backderf’s drawings are cartoony in the best way, the detailed and clear fineliner art reminding me of the work of Joe Sacco. The comic presents characters, objects and landscapes in an angular and weird fashion that is both clunky and appealing despite its simplicity.

Like the drawings, the narrative structure of My Friend Dahmer also shows Backderf’s skill as a cartoonist. The story has a distinct arc as it zooms in and out of Dahmer’s and Backderf’s lives, sometimes comparing their upbringing in juxtaposing panels. At certain points, however, the comic seems too absorbed by its own meaningfulness. Comparing Dahmer to Jack the Ripper in one unfortunate panel, or making references to the “hellish future” that awaits him are unbecomingly sensationalist and divert attention from the events as they unfold. In keeping with the advice “show, don’t tell”, My Friend Dahmer is at its best when it is at its most personal. Many of Backderf’s drawn memories are certainly haunting and bear the regret of not having known enough.

While this is certainly a graphic memoir worth reading, the question remains whether My Friend Dahmer can contribute to the demystification of its subject or merely adds yet another layer of representation to his story. While the passages that recount Backderf’s first-hand memoires certainly feel genuine and thought provoking, it is only too telling that the cover of the book’s newest edition already points to the next medium, the 2017 film of the same title. The photographed boy on the cover of my comic’s edition may look like Dahmer, but beware, it is in fact actor Ross Lynch.

My Friend Dahmer

Derf Backderf

2012

Abrams ComicArts